Palmer Memorial Episcopal Church, Houston, Texas

The Reverend Neil Alan Willard, M.Div.

Proper 15, August 16, 2015

The king went to Gibeon to sacrifice there, for that was the principle high place . . . At Gibeon, the LORD appeared to Solomon in a dream by night; and God said, “Ask what I should give you.” (I Kings 3:4-5)

One night years ago, while I was serving on the Bishop Search Committee for the Episcopal Diocese of Minnesota, there was — not surprisingly — something on my mind, something that I couldn’t seem to get my head around. That probably doesn’t happen to you, but it does happen to me from time to time. Anyway, I managed to go to sleep with all of that swirling around in my head.

At about 2:00 a.m., I suddenly awoke. I didn’t get out of bed, but I did see in my mind’s eye those things that were bothering me with much greater clarity. I could somehow see down the road a bit further than before. Miraculously, I not only went back to sleep but also remembered what had come to me in the middle of night after waking up to the sound of the alarm clock.

Now where did that clarity come from? What was its source: the subconscious, the random firing of neurons, my own intellect taking advantage of a little insomnia? Do you think it might have been God speaking to me in a dream? Or is that just crazy talk? Do you ever wonder about that, about God tilling the soil of your subconscious and allowing an insight to take root there while you’re asleep?

The world most of us have created and inhabit by choice doesn’t waste time thinking about dreams and the divine presence. The last thing we want is for voices in the night to disrupt our own little worlds that we maintain and control so carefully. We want to silence them or to drown them out with our own voices. Sure, there are things that bother us now and then, things that keep us up at night. But we can figure them out on our own. The only divine intervention we think we need is a little more caffeine. “We do well in our management while we are awake,” observes the biblical scholar Walter Brueggemann:

. . . and we keep the light, power and control on 24/7. Except, of course, that we must sleep. We require seasons of rest and, therefore, vulnerability. Our control flags. We become open to stirrings that we do not initiate. Such stirrings come to us in the night unbidden. Dreams address us. They invite us beyond our initiative-taking management. The ancient world and the biblical tradition knew about dreams. The ancients understood that the unbidden communication in the night opens sleepers to a world different from the one they manage during the day. The ancients dared to imagine, moreover, that this unbidden communication is one venue in which the holy purposes of God, perplexing and unreasonable as they might be, come to us.[1]

Maybe you’re willing to concede that God might be able to wiggle his way into the human psyche but only in the case of an important and pious person, a person such as King Solomon. After all, God probably has a lot on his plate. If that’s the case, if that’s what you really believe, you don’t know much about Solomon or the kinds of people in the Bible — or outside the Bible — whose lives are interrupted by the Holy One of Israel.

This morning’s reading from the First Book of Kings began just after a description of Solomon’s political alliance with the Pharaoh of Egypt. Solomon was ambitious, and marrying the daughter of Pharaoh was a quick and easy way of getting ahead in a world of military might. He had already ordered the execution of his rival brother Adonijah, the execution of Shimei to avenge his father David, and the execution of Joab who had done David’s dirty work in making sure that Uriah the Hittite wouldn’t return alive to his wife Bathsheba. Joab had fled to the altar, grabbing onto its horns and seeking sanctuary. But even that traditional, holy boundary wouldn’t be able to sheath the sword of Solomon’s vengeance. There, clinging to the altar, Joab was slain at the hands of someone doing Solomon’s dirty work.

With those three troublemakers in their graves, his father’s high priest Abiathar in exile, and an Egyptian queen, Solomon could finally make his humble religious retreat at the ancient shrine at Gibeon. This was the equivalent of visiting a historic church during a presidential campaign. Solomon would have arrived there with his own entourage — a few hundred slaves — and even a contribution to the potluck supper after worship — a thousand animals for sacrifice. And according to my old college Hebrew professor, this is how it worked:

Following the local custom, the king was to offer his sacrifices and then spend the night in the sanctuary where, if he is really the divine king anointed by heaven, he would be visited in a dream by the god of Gibeon. We can be sure that Solomon would not come out for breakfast without his vision [. . . and that] he turned on the royal charm to schmooze the Gibeonites into his royal corner: kiss a few babies, admire some second-rate architecture, and make himself as comfortable as he could in the temple of the god of Gibeon for the night. Such was the life of an Iron Age politician.[2]

Solomon had the campaign trail and political posturing all figured out, other things afterwards not so much. Most of his own subjects from the northern tribes would end up as slaves of his government. This forced labor was required to carry out Solomon’s building plans for military defenses, a royal palace with luxurious quarters for Pharaoh’s daughter, and a glorious temple on Mount Zion in Jerusalem. Although the ends might have justified the means in the eyes of his imperial father-in-law, things fell apart, quite literally, after Solomon’s death. The kingdom he had inherited from his father David was divided into the northern Kingdom of Israel and the southern Kingdom of Judah.

So we might be tempted to view with suspicion the report from Solomon’s lips about what took place on that night many years earlier in Gibeon. He said that God appeared to him in a dream and declared that he could have anything he wanted. He said that he asked for wisdom, “a heart that hears,” and that God granted not only that but also riches and lifelong honor. Was it all just a sad example of shameless, religious sloganeering? Was it all a profane hoax?

This is what I love about the Bible. You can’t read the Bible — actually read it — and not ask these kinds of questions. That’s because the Bible:

. . . doesn’t spare Solomon from its merciless truth-telling. . . . Despite his manifest shortcomings, Solomon was a hero in the way the Bible makes heroes. Solomon was a hero because of the God of Gibeon, who, perhaps to everyone’s surprise, turned out to be none other than the LORD of Hosts. In the Bible heroes are heroes, not because they possess Superman’s strength or Batman’s courage but because God ennobles them, because God speaks to them, because God chose them. They are not heroes because of their exalted morality or goodness or mercy, their fame, their money, their patriotism or their piety. They are heroic because God enters their lives at surprising moments and honors them with the divine presence, makes their lives, indeed, impossibly important, by participating in them. Whatever jaundiced cynicism we bring to Solomon’s little retreat at Gibeon, the Bible is sure that God spoke to the king there.[3]

God made Solomon into the wise person who has been remembered in every generation down through the ages. Solomon was still a flawed human being, hence the problems that he struggled with. You and I struggle with our own problems. The good news is that God doesn’t have to wait for us to figure out those things on our own before interrupting our lives and making our lives important. That happened to Solomon in the temple at Gibeon; and it can happen to us when we least expect it.

Nearly a thousand years later, another descendant of the house of David would also carry many burdens to his bed and fall asleep. The outward marks of royalty and wealth and privilege, however, belonged to the distant past. This was the simple bed and the deep sleep of a man who worked with his hands. During the nighttime:

. . . an angel of the Lord appeared to him in a dream and said, “Joseph, son of David, do not be afraid to take Mary as your wife, for the child conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit. She will bear a son, and you are to name him Jesus, for he will save his people from their sins.”[4]

AMEN

1 BACK TO POST Walter Brueggemann, “Holy Intrusion: The Power of Dreams in the Bible,” in The Christian Century (July 28, 2005) 28-31.

2 BACK TO POST From an undated sermon by the Rev. Fred Horton, Ph.D., at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Professor Horton taught me Hebrew and Aramaic at Wake Forest University. Interestingly, we were also students together at Wake Forest University for two semesters of Akkadian, the ancient language of the Assyrian Empire. Perhaps unsurprisingly, we were the only two students in that class. Professor Horton was also the first Episcopal priest that I came to know both as a mentor and a friend.

3 BACK TO POST Horton.

4 BACK TO POST Matthew 1:20-21.

Wonderful sermon, Neil. Thanks for posting it! I have been interested in dreams for as long as I can remember. I have kept a dream journal and truly believe God speaks to us in this way. God also heals us with our dreams, I believe. There is a brief chapter in Amy Martinez’ book, Moment to Moment, for which Roger Hutchison did the cover art, which is really to the point of paying attention. I hope you get some great conversations following such a great sermon.

LikeLike

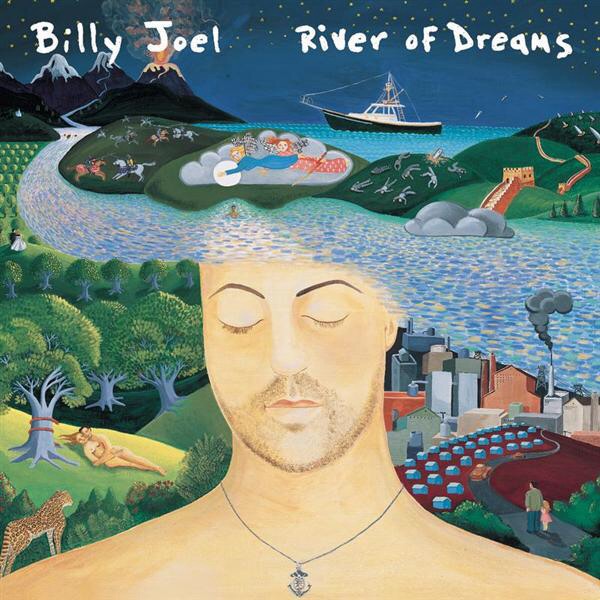

Pingback: Haiku Friday: The River of Dreams | Tumbleweed Almanac

By faith I float on

the river of dreams to awaken

refreshed and renewed.

LikeLike

This is great Neil. Thanks for sharing your gifts.

LikeLike