Palmer Memorial Episcopal Church, Houston, Texas

The Reverend Neil Alan Willard, M.Div.

Proper 15, August 17, 2025

Jesus, Savior, may I know your love and make it known. Amen.

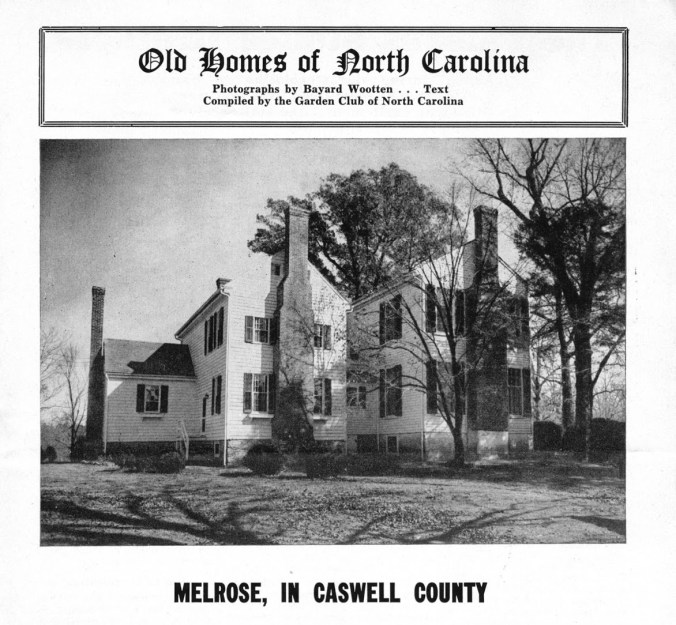

I’ve described in the past a few things about the church in North Carolina where I was baptized. It sits on more land than Palmer does, bordered in the 1970s and 1980s by two large tobacco fields. On the other two sides are roads that form a crossroads, hence the name Union Cross Moravian Church.

So there was a lot of grass to mow, which was always done by volunteers from the congregation. Daddy and I would take our turn in that work rotation, which included cutting the grass throughout God’s Acre. God’s Acre is the name that Moravian Christians use for the church cemetery, traditionally laid out in a grid pattern, with sidewalks around large squares filled with graves, each one with an equal, recumbent, white marble headstone.

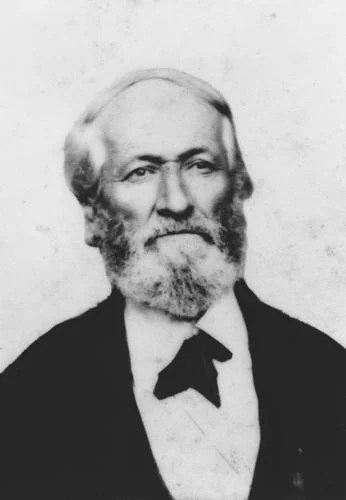

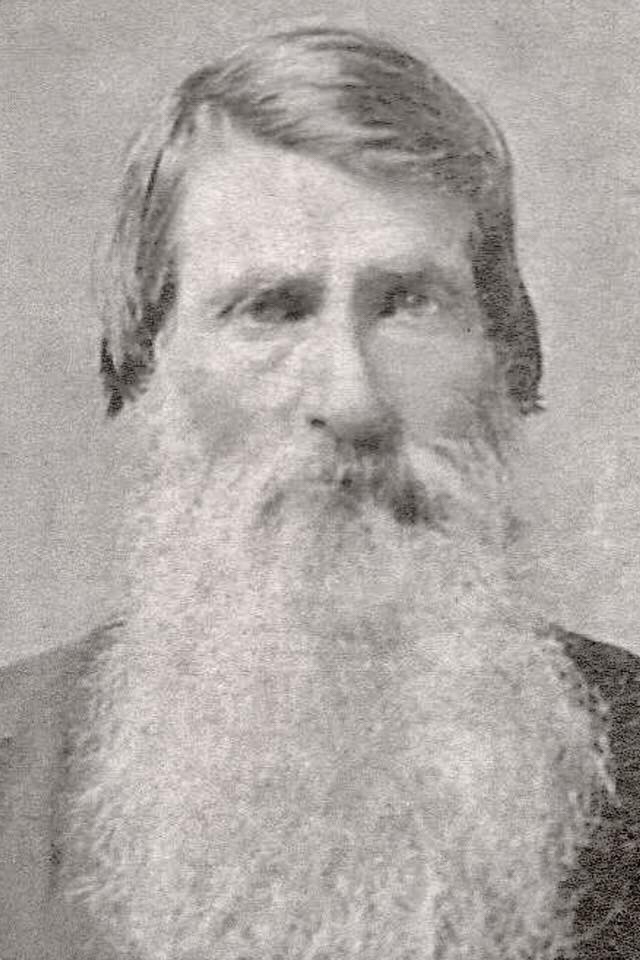

My great-grandparents are buried there, so I remember seeing their simple headstones as I walked around them with the push mower. I also remember seeing another headstone in one of the first rows of graves, which had a rare-for-that-cemetery Masonic symbol at the top of it, just above the name of J. L. Johnson.1 He had donated the land for the church in the 1890s and died in 1900. And that’s most of what I knew about him for most of my life.

I had never heard the amazing stories about Dr. John Lewis Johnson from my father because I’m pretty sure he’d never heard them from his father. Although my granddaddy was born in 1894 and surely met Dr. Johnson at some point as a small child because they lived close to one another, somewhere along the way, people just stopped talking about what had really happened in the past.2 Those memories were buried in the ground, totally forgotten at some point.

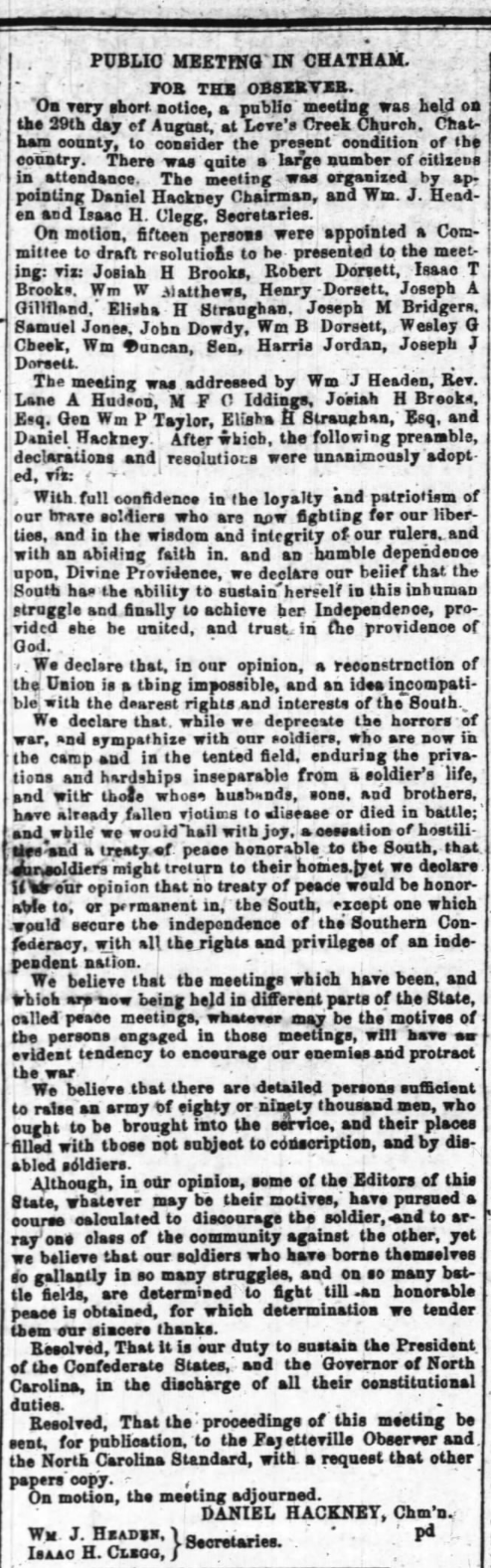

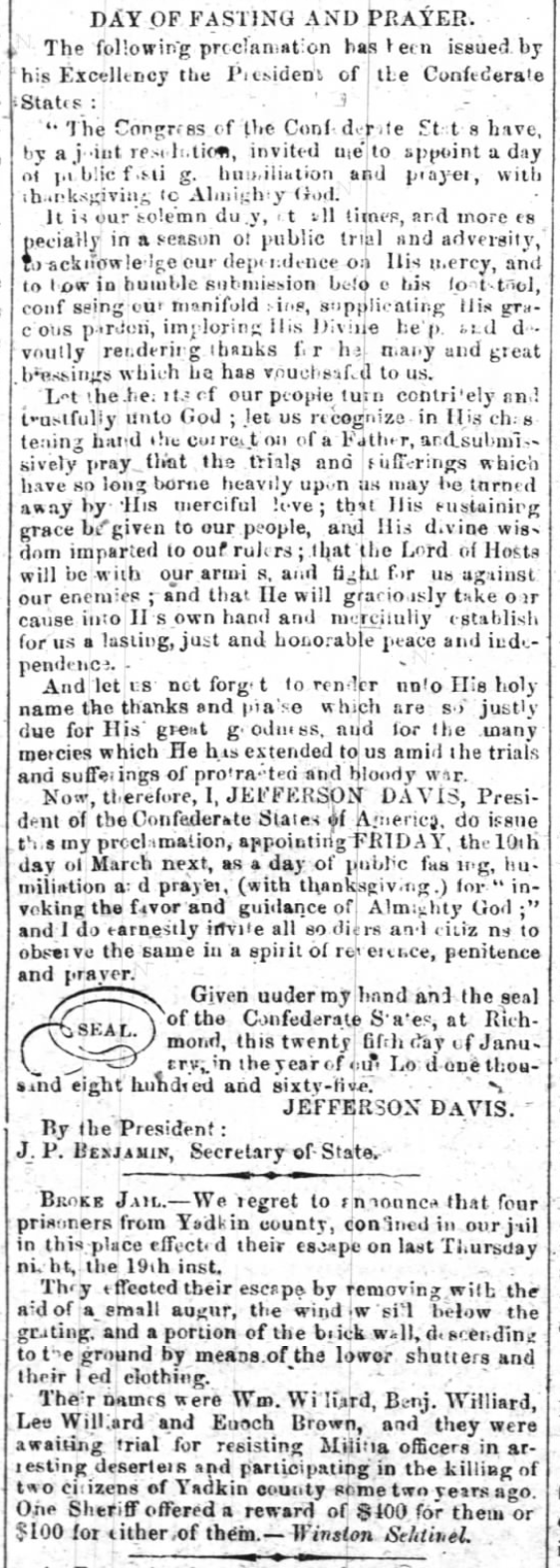

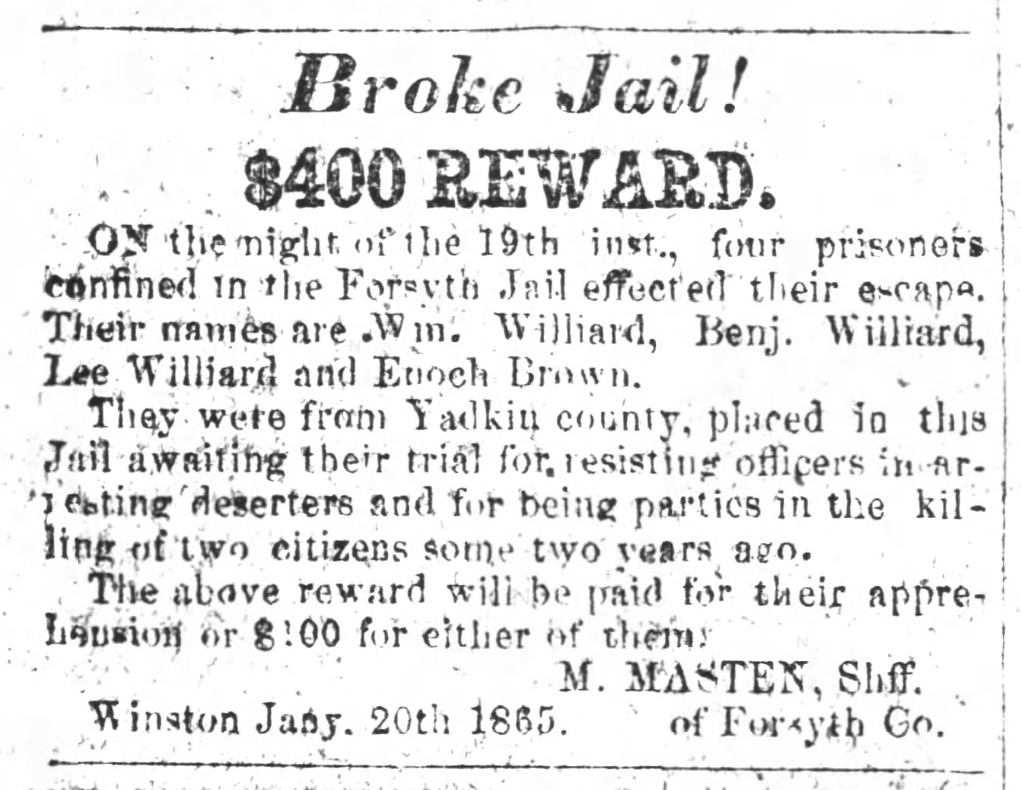

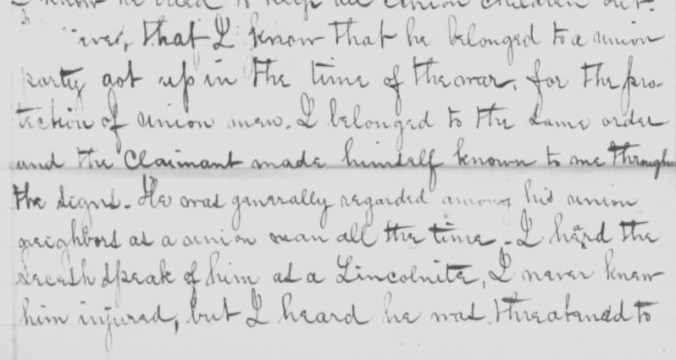

During the War of the Rebellion, there was an inner-civil war taking place not only in the mountains of North Carolina, but also in the Piedmont region, where I grew up. And Dr. Johnson was both a founder and leader of a secret society of Unionists called the Heroes of America.3

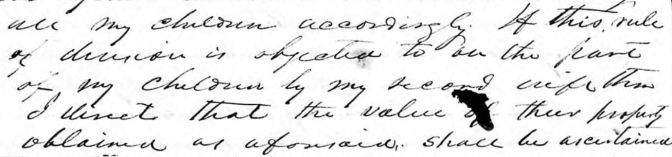

They protected and stayed connected to each other’s families. They helped young men avoid the Confederate draft, hide from the Home Guard, or make their way to the Federal lines in Tennessee. Less than two years after the end of the Rebellion, Dr. Johnson helped to draft a number of resolutions endorsed by a large gathering of loyal citizens in the Union Cross community. They expressed their love for the American flag as a “proud emblem of freedom,” embraced congressional reconstruction, advocated for political cooperation between formerly enslaved Blacks and loyal whites, and said that:

. . . we wish to see the freedmen protected in their rights of franchise, knowing that they will not raise their arms against the just power that tore from their hands the galling shackles of slavery.4

Now I’m telling you all of this for two reasons. The first is because the Heroes of America also went by a nickname — the Red Strings — which comes from a story in the Book of Joshua in which a scarlet cord was used as a secret sign to protect a woman and her household in Jericho after she helped two spies on a reconnaissance mission escape by lowering them down the city wall with a red rope.5 That woman in the Old Testament was named Rahab, and she’s listed in the roll call of faith in the New Testament’s Letter to the Hebrews.6

That roll call of faith is much longer than the partial list in the passage read a few minutes ago, which included Rahab’s name.7 But she and everyone else on that list in Hebrews stepped out into the world in faith, helping to shape the world around them in ways which reflected divine salvation or health or wholeness. Although they didn’t see the end result, they’ve been part of what God is doing in the world, just as we’re part of what God’s doing in the world.

Even though you may not see the end result of what God is doing, what God is really and truly doing through your life, you are surrounded by a “great cloud of witnesses,” as the Letter to the Hebrews puts it.8 In that crowd is Rahab, with everyone else from the pages of the Bible in the roll call of faith.

In that crowd are also people known to you from your family of birth or your family of choice. In that crowd are people whom you came to know because you were curious about the past — people who stepped out in faith during the Civil Rights Movement, during Reconstruction, during the Reformation — people who stepped out in faith by unlocking the doors as the first disciples did in the Upper Room after they had seen Jesus on the other side of death and chose to keep looking for Jesus.9 In spite of fear, they walked out those doors.

The author of Hebrews imagines us running in a stadium, with all of those people in the stands cheering us on. While keeping our eyes fixed on Jesus, we can hear the roar of that crowd as we run the race — a roar which, like the love of Jesus, is for us, not against us. We’re not alone down here on the race track.

You don’t even have to imagine that roar since you heard screams and cheers from across the street this morning as you walked through the doors of the church. New students — new Owls — are being welcomed, loudly, to the campus of Rice University. The message is that each of them belongs there, just as each of you belong at the center of the action in the stadium of faith.

But here’s the other thing, the other reason why I wanted to share with you those stories about Dr. Johnson. When people stop telling stories from one generation to another, when people stop remembering things as they really were, what had once seemed important not only diminishes but can evaporate into thin air as if it had never existed. That’s true not only for our historical memory but also for our theological memory, our Christian faith and life.

If you saw the sci-fi movie Interstellar about a dystopian future for the whole planet, you may recall Matthew McConaughey, in the role of a widowed former NASA test pilot, going to a meeting at school which included his young daughter and her teacher. The daughter had brought to the classroom an old textbook showing the Apollo missions had not been faked. But that contradicted the stories being told to future generations. Watching that scene, you see how folks are living in an alternate reality, shaped for them by others.

Christians are not born, they are made, reborn in each generation. But they will not automatically appear in future generations if we stop paying attention to that, if we think that someone else will tell our children, our friends, our neighbors, our guests within these walls the stories of faith that have led us to the present moment, if we think that others will remember the Christian past on our behalf while we choose to remember something else, perhaps how we have succeeded on our own, how we were not dependent on God’s grace.

If that is what is most important to us, something separate from Christian community, that will become most important to those who come after us. And then we will be shocked at how quickly faith starts to fade into nothingness.

Faith is something each of us can hold on to throughout the hard times, like the scarlet rope offered by Rahab — and make no mistake about it, there will be hard times, difficult chapters in our own lives and the world around us.

I mentioned earlier that Dr. Johnson died in 1900, just long enough to see much of what he had worked for and hoped for slip away before his very eyes. The only successful coup d’état in the history of the United States took place in Wilmington, North Carolina, in 1898.10 It was the culmination of a white supremacist political campaign throughout the state that year, which included threats of violence and acts of violence to keep Black citizens from voting.

An armed white mob seized control of Wilmington, expelling Black politicians and others. Before sunset, they had forced the mayor, the board of aldermen, and the chief of police to resign. A week later, the publisher of the Chatham Record newspaper, Henry A. London, wrote these words in an editorial:

Wilmington is once more ruled by respectable white men and all her citizens are now safe and secure in their lives, liberty and property.11

Then, just three months and one day before Dr. Johnson’s death, white North Carolinians, having once again kept Black citizens away from the polls, voted to approve an amendment to the state constitution which would ensure the legal disenfranchisement of most Black voters throughout the Old North State.12 It would take decades for this to become undone, and Dr. Johnson, of course, didn’t live to see that undoing.

I can’t help but believe that Dr. Johnson kept his eyes on Jesus as he ran with perseverance through this life in the midst of turbulent times and that it affected deeply the way he looked at the rest of humanity — the way he looked at his neighbors, they way he looked at those with whom he worked closely, the way he looked at the individuals and families who lived in his community. He did not, in the words of the author of Hebrews, “receive what was promised.”13 But he was faithful to the end, his work was not in vain, and his hope, a Christian hope, for a better future for all of us wasn’t unfounded.

I believe he will awaken in the likeness of Jesus when the darkness of death is dispelled by resurrection light on the Last Day, and whatever stories of the past that are true but have been intentionally forgotten will be raised up as well and remembered. Whatever is true, lovely, and merciful is not lost to God. I also believe that our lives are just as important as his life was. So like him:

. . . let us also lay aside every weight and the sin that clings so closely, and let us run with perseverance the race that is set before us, looking to Jesus the pioneer and perfecter of our faith.14

AMEN

- Moravian Christians are not buried in God’s Acre beside members of their immediate family. Men are buried next to one another in sequence, and women are buried next to one another in sequence, demonstrating in death not only equality through the uniform headstones but also the reality that they belong to the larger family of God, which is more important than their own family or their lack of a family. Although he died in 1900, it is surprising to see that Dr. John Lewis Johnson is buried next to but after my great-grandfather Charlie Tucker, who died in 1949. Dr. Johnson and his wife had first been buried elsewhere on part of his land that was not originally donated to the church but that later also became part of the church property. They were both reinterred in God’s Acre after it had been laid out at Union Cross in the 1940s. With that, Dr. Johnson and his wife both rejoined this larger family of God. ↩︎

- According to the 1900 federal census, Dr. Johnson, a widower at that point, was living with his son near the farm of my great-grandfather Jacob Williard. My grandfather Clifton Williard/Willard would have been six-years-old when Dr. Johnson died that fall on November 3, 1900. ↩︎

- William T. Auman and David D. Scarboro, “Johnson, John Lewis,” NCpedia website, 1988. One book about the larger context is Civil War in the North Carolina Quaker Belt: The Confederate Campaign Against Peace Agitators, Deserters and Draft Dodgers by William T. Auman. Another book about the larger context is Rebels Against the Confederacy: North Carolina’s Unionists by Barton A. Myers. ↩︎

- “Republican Meeting at Union Cross,” The Daily Standard (Raleigh, North Carolina), April 2, 1867, p. 3. ↩︎

- Joshua 2:1-21; 6:12-25. ↩︎

- Hebrews 11:1-39. ↩︎

- Hebrews 11:29-12:2. ↩︎

- Hebrews 12:1. ↩︎

- John 20:19-31. This passage describes how “the doors of the house where the disciples had met were locked” before they met Jesus, risen from the dead, for the first time on the evening of the same day that women had discovered his empty tomb. That empowered them to unlock the doors, cross the threshold in faith, and go into the world. ↩︎

- “1898 Wilmington Coup,” North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources website. There are many sources from which one can learn about this historical event, but I think the best book-length treatment is the Pulitzer Prize-winning Wilmington’s Lie: The Murderous Coup of 1898 and the Rise of White Supremacy by David Zucchino. Unfortunately, my public high school in Forsyth County, North Carolina, is named for Robert B. Glenn, one of the main orators for the white supremacist political campaign of 1898. Glenn was elected Governor of North Carolina in 1905 and, ironically, testified the following year in the trial of a white man accused of orchestrating the lynching of five Black men after Glenn had ordered state militia to try, unsuccessfully, to stop the murders. Glenn also took a hard line against all lynchings after the public outcry about this case. It’s an example of swinging wildly toward law and order only after violence and other illegal means had been used to establish white supremacy. Lynchings were also bad for business. ↩︎

- H.A. London, editorial, The Chatham Record (Pittsboro, North Carolina), November 17, 1898, p. 2. ↩︎

- “On this day — Aug 2, 1900, North Carolina Votes to Disenfranchise Black Residents,” A History of Racial Injustice website, The Equal Justice Initiative. Astonishingly, although nullified by the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the language requiring a literacy test to vote remains in the North Carolina State Constitution to this day despite attempts to remove it. ↩︎

- Hebrews 11:39. ↩︎

- Hebrews 12:1-2 (emphasis added). ↩︎